Lyndon Neri talks about toleration of disharmony, nostalgia as architectural practice and reflective nostalgia as new way of preserving in Spirit of Paimio 2023 Conference.

Pentimento and toleration of disharmony

Pentimento is an Italian word meaning an act of repentance, and it refers to a situation in which the artist is not satisfied with their initial image and repaints over the top with a second image.

Pentimenti can be seen by taking an X-ray of the painting defined in art history as the presence of traces of previous work. The suggestion here is that through experimental means of preservation and adaptation, we can exploit a different logic of the ruin or remnant or history as coined by Svetlana Boym. She argues that it’s not romantic, not baroque, not melancholic, but a form of toleration of disharmony.

Last year Aedes gallery in Berlin showed many of our projects from over 17 years that dealt precisely with this experimentation as a way to tell the public a suggestion that it is not final. It is an experimentation and in many ways asking the public for forgiveness. Also our installation in Venice Biennale address many of the issues we face when practicing in the new pluralistic landscape.

One can argue that this act of repentance or the constant questioning of our process, is key to resolving some of the problems we deal with today.

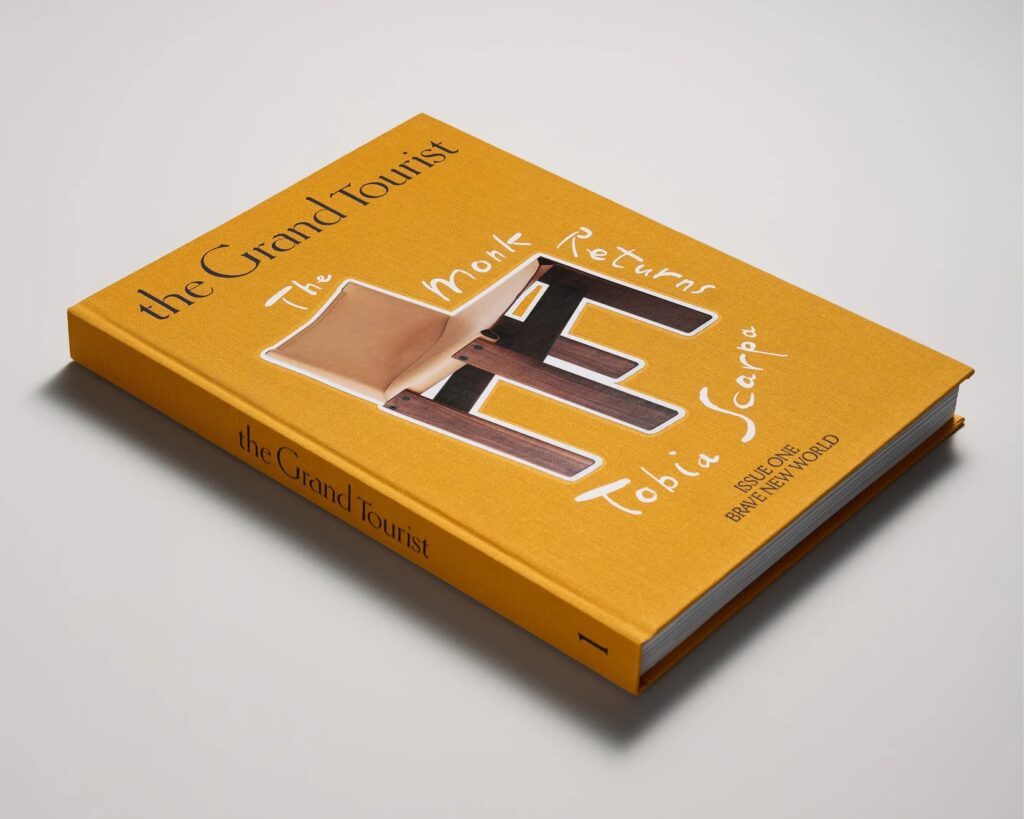

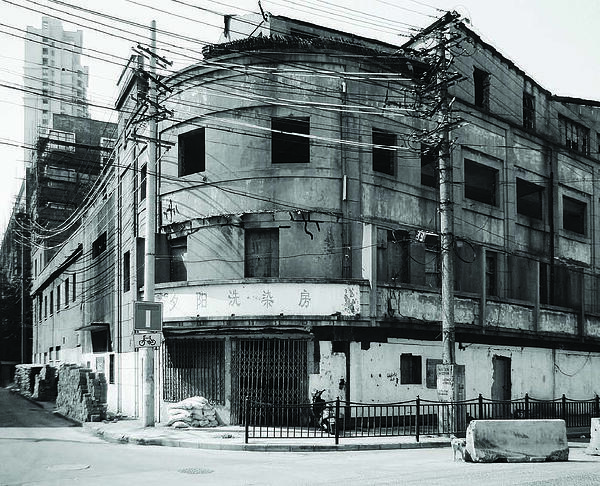

The place we come from sets the stage for many of our architectural and design exploration. This picture works as a contextual framework from which to understand our operative modes as architects, interior designers, product designers.

Architecture as a production of cultural meaning and identity

There’s an ever pressing problem in China related to the broader subject of sustainability and restoration, but it is not just a China condition, it is also a global condition. It is often discussed in terms of urban or adaptive reuse.

The intense development of the last 20 years has forced a city like Shanghai to confront with the aftermath of the demolition, of erasure of traditional, urban and cultural fabric. It also happens to be the 20 years that we’ve been practicing in the city. Related but more complex issue is architecture as a production of cultural meaning and identity.

Architects like us wish we knew the answers. When faced with loss we often retreat back to nostalgia. What do I mean by nostalgia? Many some of you Europeans probably cringe at this idea.

Nostalgia as practice

Nostos in Greek means homecoming and algos means pain or ache. Nostalgia, therefore, can be understood as a longing for home to the point of deep pain. Architecturally, it is like our desire to preserve a historic building or city to be frozen in time, like the Acropolis or perhaps in China, the Xian Terracotta warriors.

In The Future of Nostalgia Svetlana Boym called this type of attitude for preservation restorative nostalgia, a literal reconstruction of the lost home. What we were more interested as a practice is the way she thought of reflective nostalgia, which is more a longing for home, even if you may never arrive at home. It’s okay, because in the process, something innovative and creative happens.

Speaking of past history, we find that reflective nostalgia has an uncanny similarity to the eastern idea of ruins, very different from that of the West. Digging further, we find the earliest term for ruins in Chinese in the character cho, meaning a round of rubble not so much a building denoting the ruin site. It’s a topographic feature meaning you understand the essence or the narrative of the story from your grandparents or relatives or neighbor. So if you were to think of ruin rather than a physical concrete building, imagine if this was no longer here. If something so tragic happens, we have to rely on the stories of the many people that have come through here.

Unlike European architectural ruins, Chinese ruins no longer convey the original grandeur. Most of them are built in wood. When they burn down in Japan and in China, you have to rely on the understanding either through drawings and most times through the people who made them or the people who lived through it. The idea of storytelling or narrative, or the experience of the space and the phenomena of it becomes even more crucial and important. It means that the concept of ruin in China and Japan, and to a certain extent part of Asia, is an internalized concept and not the romantic aesthetic we have learned in Western art history.

To understand the duality of preserve and demolish, we turn to the Chinese phrase composed of two characters, the first meaning to shed and the second to receive.

Together they mean a willingness to let go. This points to a paradoxical sentiment, meaning both erasure and progress. It seems contradictory, and yet at the same time it’s the same.

The term creative destruction, a theory originated by economist Joseph Schumpeter, has been used to describe the condition of modern Chinese cities where demolition operates alongside rapid development. We have to face this condition whether we like it or not. As architects, we have to find a solution to deal with this rapid destruction of the city where we practice.

While erasure as a means of Chinese urban advancement is accepted by many, Rossana and I decided to start a practice based on the notion on an another way of looking at it. Does the attitude stem from a cultural relationship to history, both actual and conjectural? Perhaps there’s a way to to manage and mitigate this growth through other means of solution?

The Waterhouse as reflective nostalgia

One day about 12 years ago I got a call from a developer hotelier and he asked me if I would be interested in designing a project on The Bund. I got really excited. The ego in me said, I’m going to design one of the 33 buildings on the Bund. Well, I was wrong. It was this building.

It was on the southern side of The Bund. An existing concrete shell, that once was Japanese police headquarter. My first instinct was, let’s just demolish it. This really is no Paimio Sanatorium. Still what was really shocking to me was the next request: “Can you demolish this and design me a new brick building like the ones in Mayfair, London, in classical glory?” I was so shocked that I actually told the client that there’s something we can preserve in here. As he asked me why, I said, so you could save money.

I was lying, of course, but Chinese developers and Chinese hoteliers love oi when you say save money. So the first site visit was a decisive moment on our end. We wanted to do new buildings so much because we’ve been doing only interior design. When faced with the idea of building a brick Mayfair building, we decided to save the existing building.

The visual cues prompted us to try a different approach when turning this urban relic into a 19 room boutique hotel. We started thinking about the idea of traveling and the idea of a traveler as opposed to a tourist. In our adaptive reuse strategy, the ruin operates as the muse to elicit visceral experiences to connect to the past. However, the basis for adaptive reuse are actually non romantic relics from the past. Often they are useless leftovers in the city. The muse in question does not always follow a conventional set of aesthetic, nor of value designations. Maybe through this you will have a better understanding of the city without relying on the Wallpaper or the Michelin checklists.

Entering into the place you experience blurring of the interior and the exterior, as of the public and the private. I remember bringing my mother into this place, and the first question she asked me was: “Son, can I ask you two questions? Is this project complete?”I said it is complete. Then she continued:” have you been fully paid?’’ When I answered “yes” she said: “My son, you’re either extremely smart or your client is extremely stupid.” The importance of adaptive reuse is not fully understood. Just because something doesn’t have a label of preservation, it doesn’t need to be demolished.

The guest gains amazing views. You can actually see the rooms above, and the rooms actually look down to you. People often say: ’’Lyndon, you’re so perverted. It’s so voyeuristic.’’ But that’s exactly what happens in Shanghai! I live in a lane house where bathroom has big window, because obviously, I’m a modernist. If I forget to close the curtain, my neighbor sees me and the next morning she would say that I have gained weight. It means she’s seen me naked. In this process of relationship, you will be able to see.

This idea of voyeurism, this idea of interaction, is very much part of the being neighbor. In this sort of relationship, one room looking into the other, the dialogue between interior and exterior. The courtyard shutters are made from the recycled wood, from the original roof structure that had collapsed. The large vertical window above the reception is the cheapest room of the 19 rooms. There is a bar above. As you enter into the rooms, you actually see sort of the vitality of the community up above. We kept all the existing stairways. Some stairways lead to nowhere and rumors have it that opium was readily shared in this place, and therefore there were so many different stairs that lead you up to different places to make good hiding places. Also this project recomposed the memories of the city that would have otherwise been demolished.

The project became another way of preserving, perhaps an alternative to the idea of the conventional preservation without exactly freezing time, but building on layers, playing on the materials, surfaces, spaces, light, memories almost like building on a ruin.

After we finished this project, we lost 2 or 3 projects because a lot of people thought we were making fun of the city and many of the government projects died in front of us. It was not until two years later when David Beckham decided to rent the whole hotel, that the tourism board decided that maybe we should give it some exposure. How ironic it is! Juhani Pallasmaa stayed there, but they didn’t care, but when David Beckham stayed, all of a sudden it made a difference. That’s the sad state of where we are in terms of architecture. As a society we are more interested insort of the phenomena of the popular and the famous – two years later, this building became the front page of the tourism board of Shanghai. And after that we start getting projects.

For more info of The Waterhouse

http://www.neriandhu.com/en/works/the-vertical-lane-house-the-waterhouse-at-south-bund

Lyndon Neri co-founded Neri&Hu Design and Research Office with Rossana Hu in 2004, an inter-disciplinary architectural design practice based in Shanghai, China. Through his practice, Neri has reinforced a core vision: to respond to a global worldview incorporating overlapping design disciplines for a critical paradigm in architecture, while believing strongly in research as a design tool, as each project bears its unique set of contextual issues.

Photos: Pedro Pegenaugte