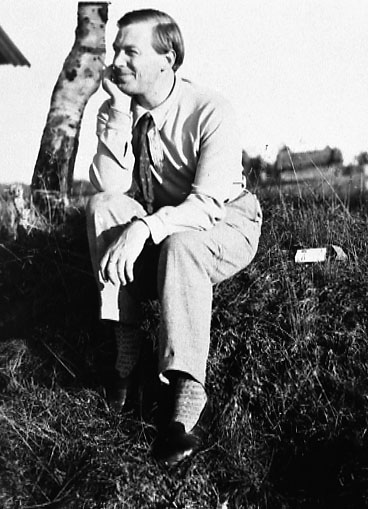

Alvar Aalto

1898-1976

“When I began designing Paimio Sanatorium, I myself happened to be ill for several months, so I was able to use myself as a test case of how an ill person’s room should actually be constructed. A person who is in a constant state of illness is naturally more delicate, more sensitive, than a normal person.”

– Alvar Aalto

Alvar Aalto (1898-1976) enjoyed an exceptionally rich and varied career as an architect and designer, both at home in Finland and abroad.

After qualifying as an architect from Helsinki Institute of Technology (later Helsinki University of Technology and now part of the Aalto University) in 1921, Aalto set up his first architectural practice in Jyväskylä. His early works followed the tenets of Nordic Classicism, the predominant style at that time. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, he made a number of journeys to Europe on which he and his wife Aino Marsio, also an architect, became familiar with the latest trends in Modernism, the International Style.

The pure Functionalist phase in Aalto’s work lasted for several years. It enabled him to make an international breakthrough, largely because of Paimio Sanatorium (1929-1933), a remarkable Functionalist milestone. Aalto had adopted the principals of user-friendly, functional design in his architecture. From the late 1930s onwards, the architectural expression of Aalto’s buildings became enriched by the use of organic forms, natural materials and increasing freedom in the handling of space.

It was characteristic of Aalto to treat each building as a complete work of art – right down to the furniture and light fittings. In 1935, Artek was formed to promote the growing production and sales of Aalto furniture. The design of his furniture combined practicality and aesthetics with series production, following the main Artek idea of encouraging a more beautiful everyday life in the home. As far as design was concerned, Aalto was driven by an interest in glass since it provided an opportunity to handle the material in a new kind of way using free forms. His win in the Karhula-Iittala glassware design competition in 1936 led to the birth of the world-famous Savoy vase.

From the 1950s onwards, Aalto’s architectural practice was employed principally on the design of public buildings, such as Säynätsalo Town Hall (1948-1952), the Jyväskylä Institute of Pedagogics, now the University of Jyväskylä (1951-1957), and the House of Culture in Helsinki (1952-1956). His urban design master plans represent larger projects than the buildings mentioned above, the most notable schemes that were built being Seinäjoki civic centre (1956-1965/87), Rovaniemi city centre (1963-1976/88) and the partly built Jyväskylä administrative and cultural centre (1970-1982).

From the early 1950s onwards, Alvar Aalto’s work focussed more and more on countries outside Finland, so that a number of buildings both private and public were built to his designs abroad.

Aino Marsio-Aalto

(Aino Aalto) 1894-1949

Aino Marsio (1894-1949), the rationalist architect and designer, graduated from Helsinki University of Technology 1920. She worked briefly in the office of the architect Oiva Kallio in Helsinki, moving to Jyväskylä in 1923, where she initially worked as a draughtsman in the office of the architect Gunnar A. Wahlroos. She moved to Aalto’s office at the start of 1924, and Aino and Alvar Aalto were married in October of that same year. Her talent and skills were transcending architecture and exploring various forms of design.

Aino Aalto worked alongside her husband as a designer of equal standing. Many competition entries were submitted jointly by Aino and Alvar, such as those for the Paris International Exhibition and New York World’s Fair pavilions. In the extensive output of Aalto’s office it is, however, hard to distinguish the roles of the different designers, since works mostly went by the name of the office.

Aino Aalto was especially interested in interior and furniture design, for which she had plenty of opportunities in Aalto’s office’s comprehensive building projects like Paimio Sanatorium. The aspiration to beauty, quality and utility made Aino a remarkable interior designer. As Artek’s first Design Director, Aino Aalto created the company’s still-recognizable, timeless, high-quality style. Indeed, Maire Gullichsen described her as the most aesthetic person she had ever met.

At the Milan triennial 1936 she won the Grand Prix medal for the design of the stand as well as at the design competition in glass 1932 which she championed with glass sets Bölgeblick. The set was inspired by the motion of a stone thrown in water. Besides it’s pleasing aesthetic, it is very functional, stackable and affordable due to the usage of a cheap glass. Glass sets express the concept of elastic standardization, her design philosophy perfectly – making design pieces attainable to the wider public by conceptualizing a product as a symbiosis of an optimised material usage and anartistically valuable form.

Alvar Aalto’s biographer Göran Schildt portrays Aino as the ultimate judge and the end filter of Alvar Aalto’s architectural works. More genuine design credit is given to her in interior design of the studio, as well as the fruitful furniture and product design. Along with the glass design for Iittala, furniture pieces produced by Artek, nowadays make a substantial part of the Nordic design heritage.

Among the notable interior projects of Aino Aalto, is couple’s own home in Helsinki’s Munkkiniemi. She also designed some buildings independently, such as the family’s summer residence, Villa Flora, in Alajärvi (1926) and Noormarkku Children’s House and Health Center (1945).