If you can make it there, you’ll make it anywhere.

Alvar Aalto’s reputation grew in the USA following the invitation to hold a retrospective exhibition of his works at the MoMA in New York in 1938, which was his first visit to America. The significance of the exhibition, which later went on a 12-city tour of the country, is in the fact that he was the second-ever architect, after Le Corbusier, to have a solo exhibition at the museum. It cemented him as member of modernist big five along with Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, J. J. P. Oud and Le Corbusier.

“The exhibition of furniture and architecture by Alvar Aalto presents the first American survey of the work of the Finnish architect, who is recognized as one of the most important and original modern architects and furniture designers of the past decade.” The press release of exhibition promised.

Aalto: Architecture and furniture was not just first American survey, it was the very first survey. The exhibition already then firmly positioned Alvar Aalto as a skillful synthesizer and “total” designer, his architecture walked hand in hand with the furniture. The exhibition was one of major turning points in Aalto’s career but also in Finnish design, even though it wasn’t blockbuster of any kind among the audiences. Those who mattered most, architecture and design professionals and investors, were deeply impressed.

Manifestation of modern movement on its pre-war peak

On a hindsight MoMA’s Aalto: Architecture and furniture presented a magnificent snapshot of the way the modern movement was blossoming in the final days before the start of World War II. It was also a manifesto of hope and optimism of the 1930’s. Aalto was a firm believer that buildings have a crucial role in shaping society. By the end of 1930’s Alvar Aalto’s take on modernism was not only influenced by the landscape of his native country, but by the political struggle over Finland’s place within European culture.

“Aalto’s designs are the result of the complete reconciliation of a relentless functionalist’s conscience with a fresh and personal sensibility. This reconciliation demands tact, imagination and a sure knowledge of technical means; careful study of Aalto’s buildings show all three in abundance”, John McAndrew, the Museum’s Curator of Architecture and Industrial Art wrote about Aalto.

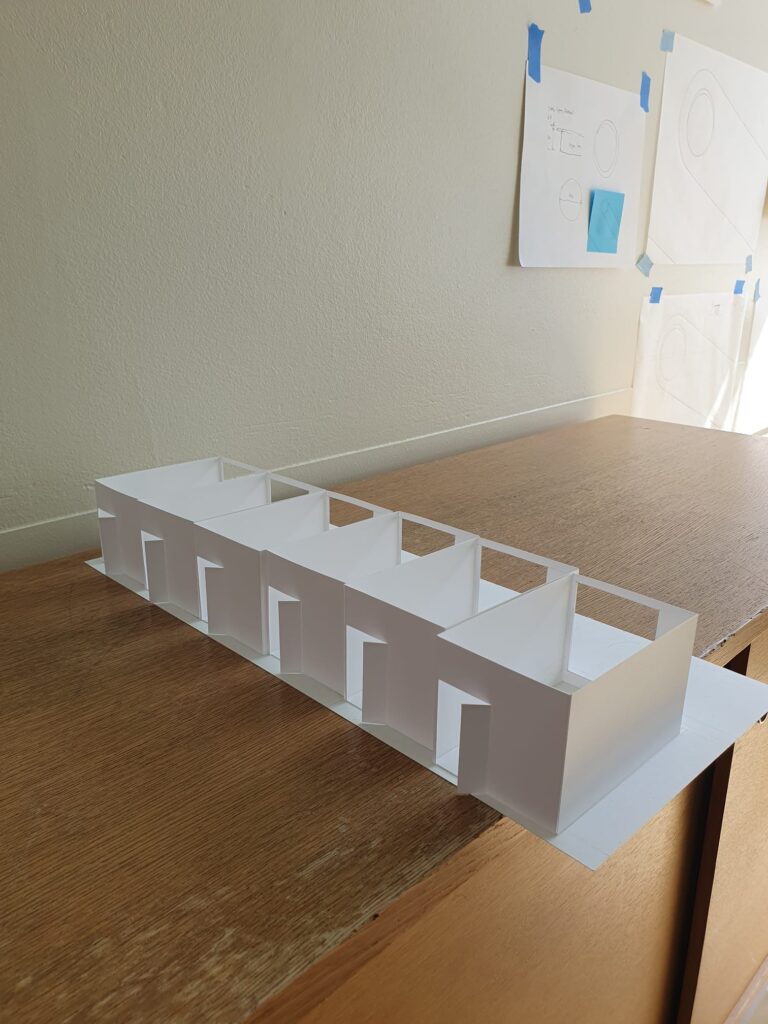

Spread in three big rooms the exhibition included enlarged photographs, air views, drawings, and models of Aalto’s architecture and a detailed study of four of his then finest buildings: Paimio Sanatorium, Vyborg library, the architect’s own house in Helsinki and the Finnish Pavilion for the Paris 1937 Exposition, which was one of the key triggers of the MoMA invitation.

Interiors on the front line

Exhibition highlighted Aalto’s fascination with the interior life of his buildings. Also his search for architectural and environmental consistency, and for a fusion of exterior and interior spaces, that led him to design chairs, furnishings, fabrics, glassware, and other domestic items was strongly manifested as round 50 pieces of furniture was also exhibited.

“In his furniture, the audacious manipulation of wood might be thought bravura were it not always justified by the physical properties of the material. As in his architecture, Aalto’s designs are a result of the same combination of sound construction, suitability to use and sense of style.”

Some of Aalto’s grandest innovations were realized in his interiors, and it was in the use of wood that he found a material to reinforce an emerging esthetic direction. Wood could be simple and direct, and yet possessed an inherent warmth. Aalto disliked cold, austere qualities of Modernism. With wood, he found a way to combine the best qualities of Modernism with organic abstraction. At a time noted for dogma and inflexible Modernism, Aalto demonstrated that Modernism was not simply one route but many paths.

That of course, is the key feature of Aalto’s furniture. While he always sought to satisfy specific conditions, all his furnishing designs had a broader application. One of his greatest assets as a designer was his ability to be near and farsighted at the same time. Aalto’s concepts used standardized parts and serial production suggests that his good fortune stemmed from a calculated shrewdness rather than from luck and a favorable market.

The furniture section also included glassware and lighting fixtures which Aalto designed for the Paris 1937 Exposition and several of his abstract wood designs were used as wall decorations.

Aalto’ design philosophy and standardization made a deep impact on John McAndrew.

“A major distinction of the furniture is its cheapness. Low-cost housing of good modern design has been produced for the last fifteen years; now, probably for the first time, a whole line of good modern furniture is approaching an inexpensive price level.”

America, here I come

During his exhibition tour, Aalto also gave lectures for the first time in the United States. Lectures were held at Yale University, New York University, and even at MoMA. Aalto’s proficiency in English had not yet reached its peak, although he had put in a lot of work with Linguaphile exercises and he also had practical experience from his recent trip to London. Linguistic shortcomings he compensated with sparse but precise commentary on the images and with his charismatic, made to measure personality for American audiences. All the lectures were great successes.

The exhibition at MoMA laid a solid foundation for Aalto’s major breakthrough in the United States. The circles associated with MoMA provided Aalto with the networks necessary for success. The museum’s exhibitions also had a societal renewal aspect. Aalto once said, “The duty of the architect is to give life a more sensitive structure.” Americans were ready to listen what doctor needed to order.