In the darkest times of history Alvar Aalto found home for his optimism and humanism, but also next phase in his practice in America.

Despite his now mythic status in Finland now, Alvar Aalto felt unappreciated in his homeland. His boat, which he had designed and built, was named Nemo Propheta in Patria. At one point he considered moving to America. He never moved but he did, however, do two stints as a visiting professor at MIT in the 1940s and for that Cambridge campus that he created Baker House, one of his most important works.

Alvar and Aino Aalto in New York.

Alvar Aalto was tempted by the success of European modernists such as Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe. The dapper, charming Finn loved America. He was also a great fan of Frank Lloyd Wright. After meeting him Aalto changed completely as a person. Gone was the casual Finnish country attire, replaced instead with double-breasted suits. His personality suited America perfectly.

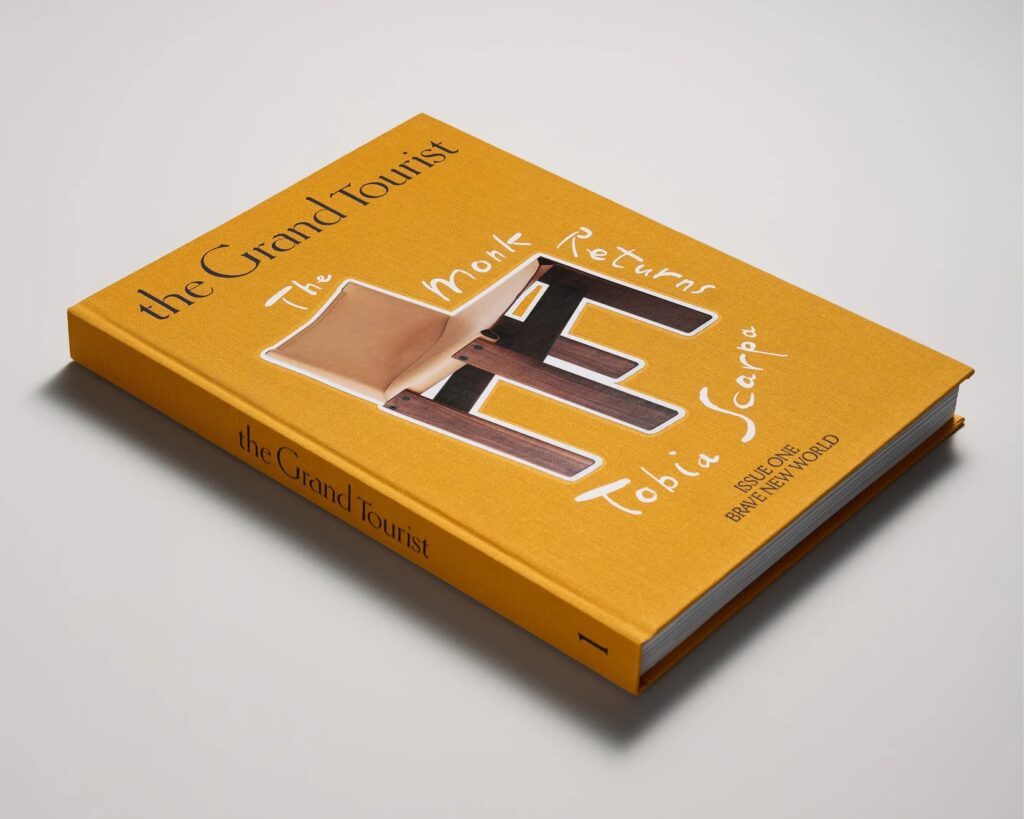

Aalto’s charming, amiable nature and skill in networking, storytelling and acting earned him a reputation as a sought-after speaker but also friendship with Laurance Rockefeller. That friendship led to the first museum exhibition and publication devoted to his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1938. In the exhibition Alvar Aalto: Architecture and Furniture MoMA placed Aalto among the key figures in modern architecture and design. It catapulted Aalto into the fame in USA and he also became involved with wealthy circles associated with the museum.

The Finnish Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair 1939.

Next year The Finnish Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair was a sensation, leading Aalto furniture designs to become the single most popular brand of modern furniture in the US until the end of the 1940s. The extraordinary success of pavilion with notable use of wood elements inspired by the Finnish forests and evoking a pre-industrial spirit and sense of freedom, brought him also international recognition. His architecture, bent-wood furniture, and the world premiere of colorful curvilinear glass vases made obvious a fresh, organic quality that owed more to nature than to any historical precedents or machine industry.

The Finland Pavilion and MoMa Exhibition introduced Aalto’s pioneering style to country and established his reputation among his American peers. Following the exhibition, Aalto received invitations from prestigious universities in the United States.

The outbreak of the Second World War was a shock for the optimistic Aalto, in whom the idea of the new and better world represented by the United States still lived strongly.

His sense of social responsibility made him begin to search for new approaches; how was Finland going to rebuild after the war? He put a good deal of effort into the development of prefabricated housing and into master planning. In this he received plenty of stimuli in America, in his capacity as visiting professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

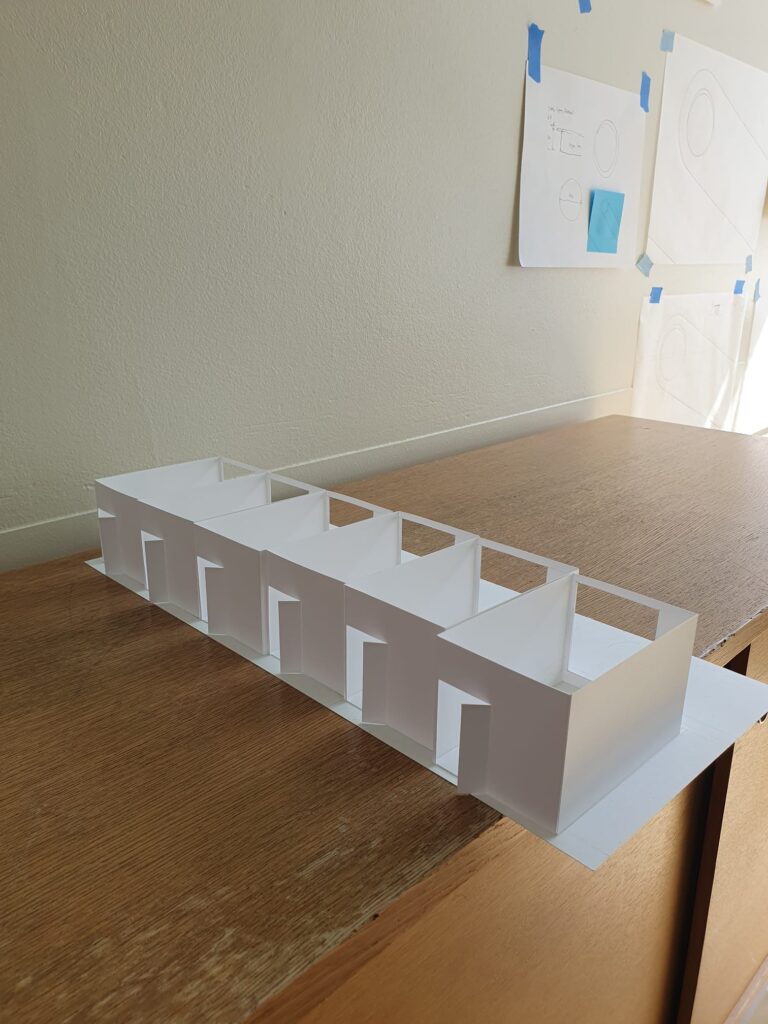

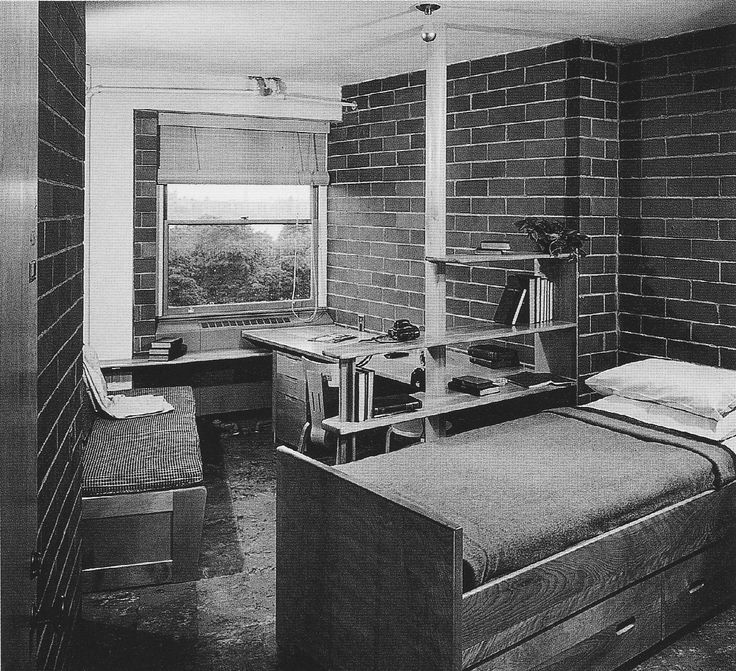

Aalto began designing his first building to be constructed abroad, the student dormitory building for MIT. There he continued the consideration of organic forms that had been interrupted by the war. For Aalto, the building opened up a new way of using brick as a material for urban architecture.

Baker House and it’s celebrated brick wall.

Baker House marked by an unconventional undulating façade of red brick, lumps of misshapen, scorched bricks a material that references the building’s Boston surroundings and giving it a warty look to the long wall that winds its way along the Charles River.

“The lousiest bricks in the world,” is how Alvar Aalto described the local New England materials he used for the building. It was meant as a compliment – he loved their twisted, blackened, brutish texture, which gave the walls the look of coarse tweed.

Prioritizing the lived realities of student experience over a rigid, singular, aesthetic language informing the whole structure, building demonstrates an openness toward the flexible potentials inherent in communal living. It’s a reconceptualization of residential life that is fabricated into the urban campus of MIT that involves a fluid form of space and materiality to understand the human experience in his architecture.

New horizons in communal living.

Following the 1949 completion of the Baker House dormitory Aalto’s visits to US became much more infrequent. Only one building, the new library of the Mount Angel Abbey, was completed after that. Aalto became disillusioned with both the American dream and the American architectural commissioning process. After stressful years between 1938 and 1948, extremely unsettled period in Finland’s history, with a destabilizing effect on Aalto, he settled down again at home. From 1950 onwards Aalto was in increasing demand in Finland, which became his primary focus for the last 26 years of his life.

America and Baker House marked one of the major turning points in his position as an architect developing his design vocabulary, his exploration of materials, and an architecture that responds to the landscape. Aalto’s designs had a lasting impact on American modernism, but his experiences in America, a place where his optimism and humanism thrived during dark times, also profoundly influenced his own stylistic development.

Baker House was turning point in Alvar Aalto’s practice.